Through my time at Fender, most of my involvement was product development, prototype development and specialties. This first article is about prototypes in general and one in particular. Since I am in the business of making headless basses I have chosen to tell of a Fender project which was never produced but one that surprised me the first time I saw it – the first Fender headless bass. We are all probably familiar with the very first Telecaster guitar by now, as it has been written about extensively and seen at guitar shows around the country. That Telecaster’s importance to me lies in the fact that there was a time when it was unique, the one and only Tele on the planet. From the guitar making standpoint, I view it as the most valuable of all Tele’s in existence. Other Teles were made famous by musicians and events but this one, the prototype, represents the hands on creation of Leo Fender’s and George Fullerton’s effort. It is also important that the guitar can be authenticated, especially as George Fullerton has done. Owning a prototype is also like owning the story that goes along with it.

Prototypes are very rare indeed. They are usually retained by the owner, founder, inventor, company or the immediate family for historical or person reasons. Sometimes they are lost, sold, given away or destroyed, their true value not being realized at the time they were built. But you can bet that prototypes exist or existed for all those many types of guitars now on the scene. Leo Fender was not sentimental about his prototypes and destroyed many of them.

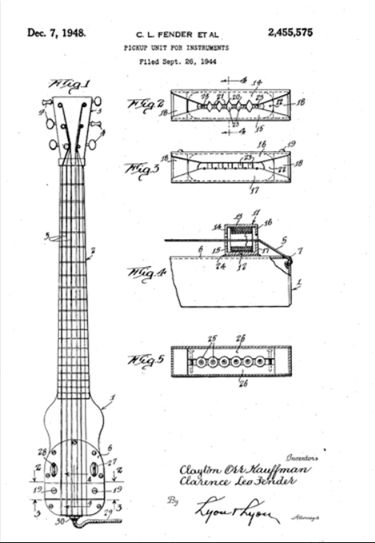

Pickup Unit Patent Drawing filed Sept. 26, 1944

A few years ago I went to the Arlington Vintage Guitar Show and bumped into a friend I had known from my years at Fender’s Research and Development Department, Gene Fields. We had not seen each other for 20 years. So we grabbed a cup of coffee and sat down for a talk.

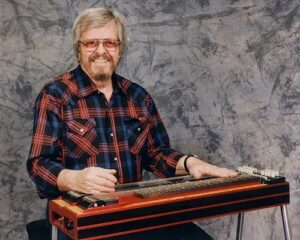

First of all, let me tell you about Gene. Gene was with Fender Musical Instruments Research and Development Department for 23 years! His designs include the P.S. 210K Keyless Pedal Guitar, the Starcaster Thinline hollow body guitar and the 2nd generation Marauder guitar. He also worked with Leo Fender on the Mustang Bass, the Musicmaster bass, the Bronco and others. His last six years with Fender were in the String Division. There he was responsible for the introduction of automatic string winding machinery into the production line, the development of several sets of guitar and bass strings and was involved with machining and testing of strings.

Gene Fields and his Pedal Steel Guitar

He joined Sierra in Portland, Oregon in 1984 designing guitars and basses before moving to MCI Intertech as General Manager of the Pedal Steel Guitar Division. After two years with MCI, the company was sold to the Fred Gretch Company. Rather than relocate again, Gene Formed “GFI Musical Products” in Arlington, Texas, building high quality pedal steel guitars.

As I told Gene about my company, Philip Kubicki Technology, which manufactures “headless” and key headed Factor Bass Guitars, he said he had something interesting to show me. I was amazed when he produced a Fender headless bass. I never knew the project existed because it was developed in 1975 after my time at Fender. I asked Gene to explain how this instrument came to be.

Historically, the first electric basses were originally developed as a smaller, lighter, more portable instrument to substitute for the upright bass, with a similar sound. These early instruments were fitted with strings made with a nylon filament running along the steel core, inside the winding, to purposely eliminate some of the sustain to mimic an upright bass sound.

As the years went by and music changed, bass players demanded a brighter sound. String manufacturers responded with roundwound and flatwound strings with as many as three layers of wrap. This produced a new problem. The bright accentuated the “dead spot” phenomenon found in some basses, on the G string at the 5th or 6th fret.

Gene was asked to research the cause of this problem and eliminate it if possible. He tried many things including double truss rods, all maple bodies, un-carved necks to make them stiffer as well as a multitude of different strings. Gene wanted a stronger, more rigid neck, so he made one of solid aluminum. All this research resulted in making the dead spot move to new areas of the neck. The aluminum neck caused the dead spot to move up to the 7th fret. This was the information Gene was looking for as this told him that the dead spot was a result of the resonant frequency of the neck. At this point Gene attached a 1 ½ pound C clamp to a stock P bass neck as ballast to dampen neck vibration. This had the effect of moving the dead spot down in frequency and almost disappear. As most key headed bass guitars are head heavy to begin with, adding weight to the head was out of the question. An opposite approach was to lighten the head of the neck. Gene took a stock precision bass neck and removed all the keys except for the first string. This moved the dead spot up in frequency but did not eliminate it. Then Gene installed the first string in the fourth string position, removed three keys and began sawing off pieces of the head, one inch at a time. Each time additional weight was removed from the head of the neck, the dead spot would move up in frequency. Then Gene removed the last key, cut all but 1” of the head off, drilled a hole for the ball end of the string and rigged a way to tune the string with a clamp on the body. The dead spot moved to about the 14th fret to the point of no longer being a problem.

In 1975, Gene’s research led to his designing a completely new instrument. This was the first Fender prototype headless bass. The concept consisted of a maple neck through body with mahogany wings. The neck has a 32” scale with 23 frets and black position markers. The body was cut to a stylized Jazzmaster shape with a carved top similar to the “LTD” Jazz Guitar. The body mounted tuner was a simple right angle pull design with tuning knobs in the tailpiece. Individually adjustable bridge sections were used as well as individually adjustable mutes. The neck pickup was humbucking while the bridge pickups were Precision bass with a special cover. The switches provided pickup one, pickup two, or both as well as phase reversal.

This instrument was field tested with very good results, but marketing thought it was too radical for its time. It was never produced. Eventually, the bass was given to Gene by Bill Schultz, Freddie Tavares and Dan Smith of Fender and is still in his possession.

The Songwriter

Sometimes prototypes are shrouded in stories and lost in development with no positive identification possible, only expert opinions to verify their authenticity. Because of the developmental nature of invention, prototypes are built, changes are made, then they are abandoned to build a new model incorporating the new ideas – each better than the one before until everything that was learned, solved and designed is incorporated into the last of a series of prototypes. The better the engineering and marketing synergy, the smaller the development time. The product cannot be shown publicly before any patents are applied for. Market testing must be done in secret. Generally, if market testing indicates that the product is salable, the patent process is initiated. Conversely, if the market testing proves that the instrument will not sell, it is abandoned. These types of prototypes are even rarer because their value at the time of their creation becomes nil because they are not treasures. They are put away and forgotten. Fender’s Marauder, Mod and Rocker, and Songwriter are examples of abandoned prototypes. The abandoned prototype does define the experimental parameters of product development.